23 Exercise 7: Sampling text information

23.1 Introduction

The hands-on exercise for this week focuses on how to collect and/or sample text information.

In this tutorial, you will learn how to:

- Access text information from online corpora

- Query text information using different APIs

- Scrape text information programmatically

- Transcribe text information from audio

- Extract text information from images

23.2 Online corpora

23.2.1 Replication datasets

There are large numbers of online corpora and replication datasets available to access freely online. We will first access such an example using the dataverse package in R, which allows us to download directly from replication data repositories stored at the Harvard Dataverse.

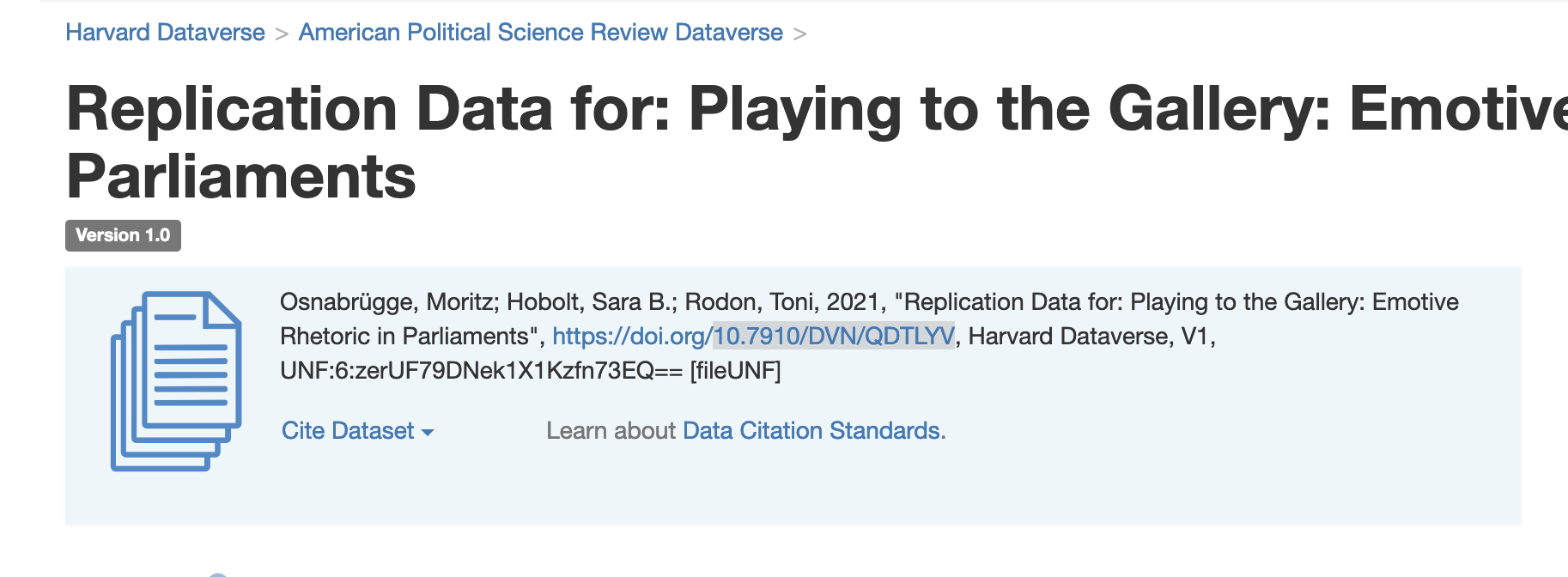

Let’s take an example dataset in which we might be interested: the UK parliamentary speech data from

We first need to set an en environment variable as so.

Sys.setenv("DATAVERSE_SERVER" = "dataverse.harvard.edu")We can then search out the files that we want by specifying the DOI of the publication data in question. We can find this as a series of numbers and letters that come after “https://doi.org/” as shown below.

dataset <- get_dataset("10.7910/DVN/QDTLYV")

dataset$files[c("filename", "contentType")]## filename

## 1 emotive_cloud.tab

## 2 neutral_cloud.tab

## 3 neutral_ireland.tab

## 4 emotive_ireland.tab

## 5 neutral_uk.tab

## 6 emotive_uk.tab

## 7 commons_stats.tab

## 8 ireland_data.csv

## 9 3-word_clouds.py

## 10 4-trends.R

## 11 8-histogram.R

## 12 1-uk.do

## 13 6-barplot_topics.R

## 14 7-plot_media.R

## 15 2-ireland.do

## 16 5-predictive_margins.R

## 17 uk_data.csv

## 18 README.docx

## contentType

## 1 text/tab-separated-values

## 2 text/tab-separated-values

## 3 text/tab-separated-values

## 4 text/tab-separated-values

## 5 text/tab-separated-values

## 6 text/tab-separated-values

## 7 text/tab-separated-values

## 8 text/csv

## 9 text/x-python

## 10 type/x-r-syntax

## 11 type/x-r-syntax

## 12 application/x-stata-syntax

## 13 type/x-r-syntax

## 14 type/x-r-syntax

## 15 application/x-stata-syntax

## 16 type/x-r-syntax

## 17 text/csv

## 18 application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.documentWe choose to get the UK data from these files, which is listed under “UK_data.csv.” We can then download this directly in the following way (this will take some time as the file size is >1GB).

data <- get_dataframe_by_name(

"uk_data.csv",

"10.7910/DVN/QDTLYV",

.f = function(x) read.delim(x, sep = ","))Of course, we could also download these data manually, by clicking the buttons at the relevant Harvard Dataverse—but it is sometimes useful to build in every step of your data collection to your code documentation, making the analysis entirely programatically reproducible from start to finish.

Note as well that we don’t have to search out specific datasets that we already know about. We can also use the dataverse package to search datasets or dataverses. We can do this very simply in the following way.

search_results <- dataverse_search("corpus politics text", type = "dataset", per_page = 10)## 10 of 38345 results retrieved

search_results[,1:3]## name

## 1

## 2 "A Deeper Look at Interstate War Data: Interstate War Data Version 1.1"

## 3 "Birth Legacies, State Making, and War."

## 4 "CBS Morning News" Shopping Habits and Lifestyles Poll, January 1989

## 5 "Common Sense" for Ontario: Defining the New Government's Mandate: June 1995

## 6 "Cuadro histórico del General Santa Anna. 2a. parte," 1857

## 7 "Don't Know" Means "Don't Know": DK Responses and the Public's Level of Political Knowledge

## 8 "El déspota Santa-Anna ante los veteranos de la Independencia," 1844 Diciembre 09

## 9 "European mood" bi-annual data, EU27 member states (1973-2014), Replication Data

## 10 "Government Partisanship and Electoral Accountability" Political Research Quarterly 72(3): 727-743

## type url

## 1 dataset https://doi.org/10.6141/TW-SRDA-C00271-1

## 2 dataset https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/E2CEP5

## 3 dataset https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/EP7DXB

## 4 dataset https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR09230.v1

## 5 dataset https://doi.org/10.5683/SP2/OKNWMZ

## 6 dataset https://doi.org/10.18738/T8/Z0JH2C

## 7 dataset https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/G9NOQO

## 8 dataset https://doi.org/10.18738/T8/U71QSD

## 9 dataset https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/V42M9J

## 10 dataset https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/5OG9VV23.2.2 Curated corpora

There are, of course, many other sources you might go to for text information. I list some of these that might be of interest below:

- Large English-language corpora: https://www.corpusdata.org/

- Wikipedia data dumps: https://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Data_dumps

- English version of dumps here

- Scottish Corpus of Texts & Speech: https://www.scottishcorpus.ac.uk/

- Corpus of Scottish modern writing: https://www.scottishcorpus.ac.uk/cmsw/

- The Manifesto Corpus: https://manifesto-project.wzb.eu/information/documents/corpus

- Reddit Pushshift data: https://files.pushshift.io/reddit/

- Mediacloud: https://mediacloud.org/

- R package: https://github.com/joon-e/mediacloud

Feel free to recommend any further sources and I will add them to this list, which is intended as a growing index of relevant text corpora for social science research!

23.3 Using APIs

In order to use the YouTube API, we’ll first need to get our authorization token. These can be obtained by anybody, with or without an academic profile (i.e., unlike academictwitteR) in previous worksheets.

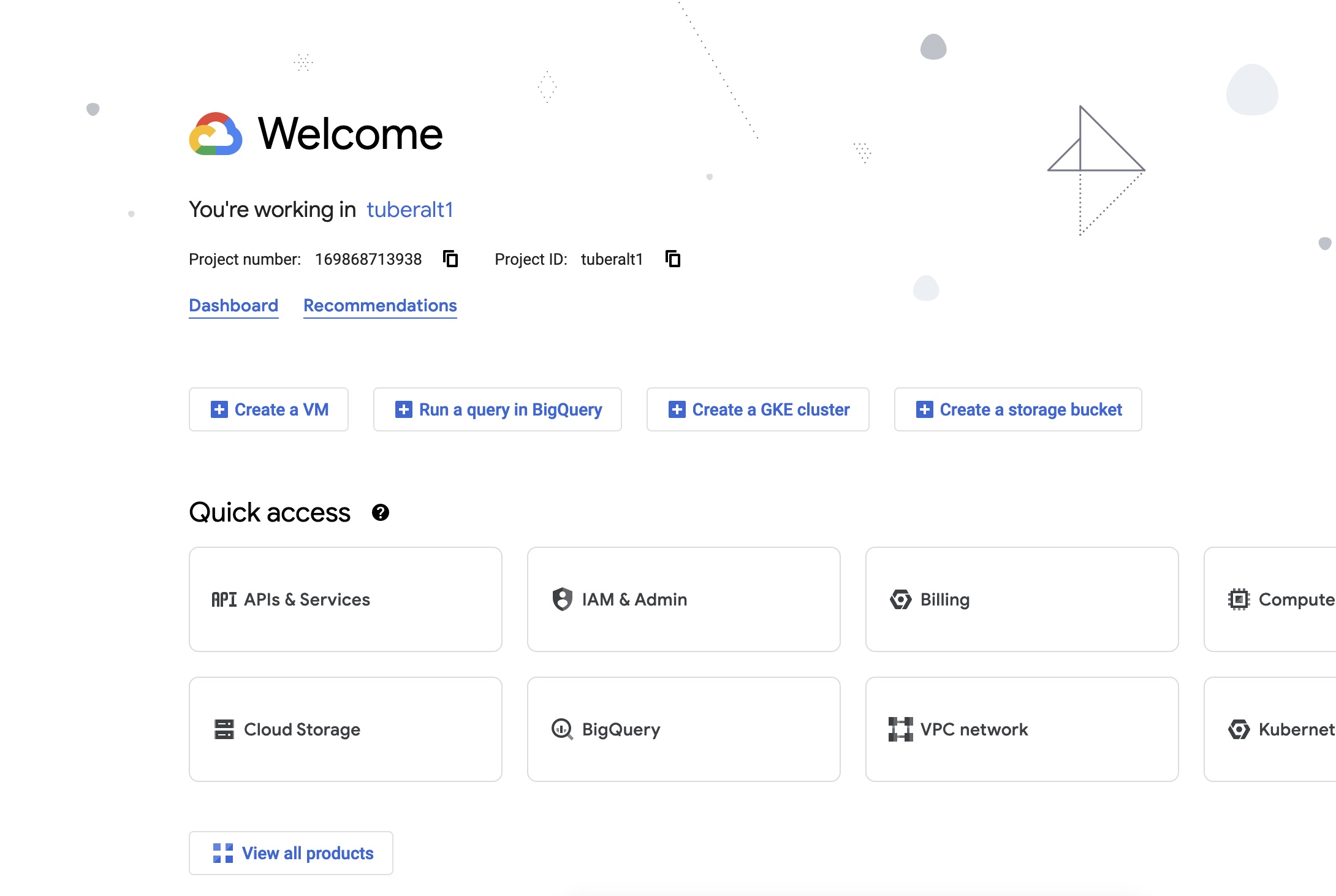

In order to get you authorization credentials, you can follow this guide. You will need to have an account on the Google Cloud console in order to do this. The main three steps are to:

- create a “Project” on the Google Cloud console;

- to associate the YouTube API with this Project;

- to enable the API keys for the API

Once you have created a Project (here: called “tuberalt1” in my case) you will see a landing screen like this.

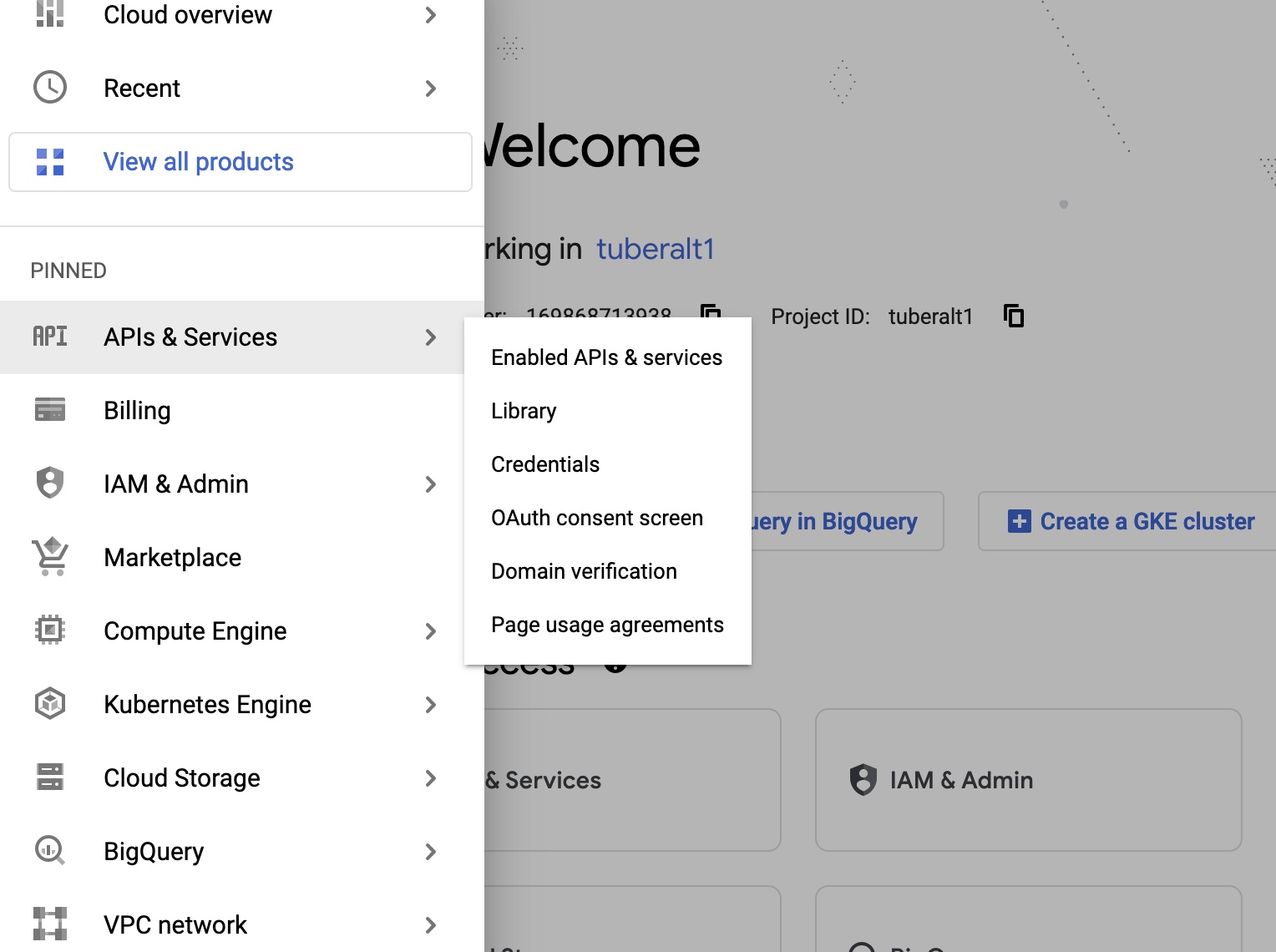

We can then get our credentials by navigating to the menu on the left hand side and selecting credentials:

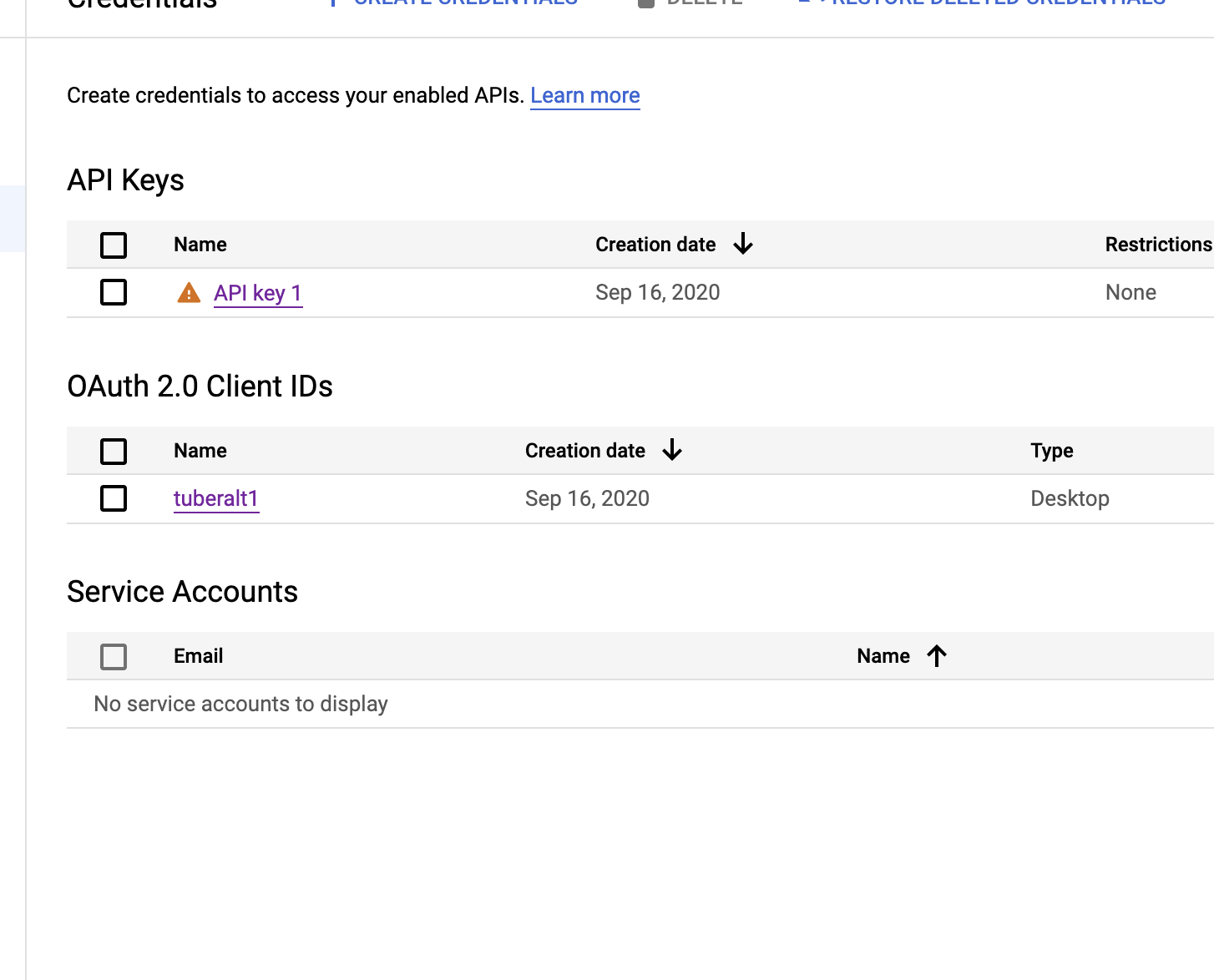

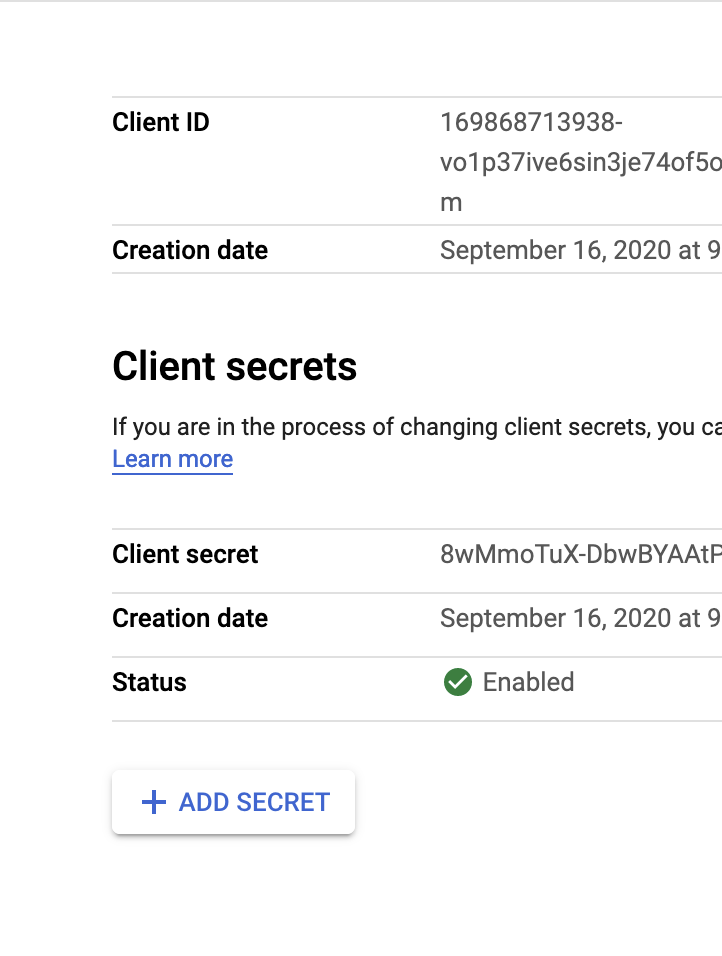

Now we click on the name of our project (“tuberalt1”) and we will be taken to a page containing two pieces of information: our “client ID” and “client secret”.

The client ID is referred to below as our “app ID” in the tuber packaage and the client secret is our “app secret” mentioned in the tuber package.

Once we have our credentials, we can log them in our R environment with the yt_oauth function in the tuber package. This function takes two arguments: an “app ID” and an “app secret”. Both of these will be provided to you once you have associated the YouTube API with your Google Cloud console project.

23.4 Getting YouTube data

In the paper by Haroon et al. (2022), the authors analyze the recommended videos for a particular used based on their watch history and on a seed video. In the below, we won’t replicate the first step but we will look at the recommended videos that appear based on a seed video.

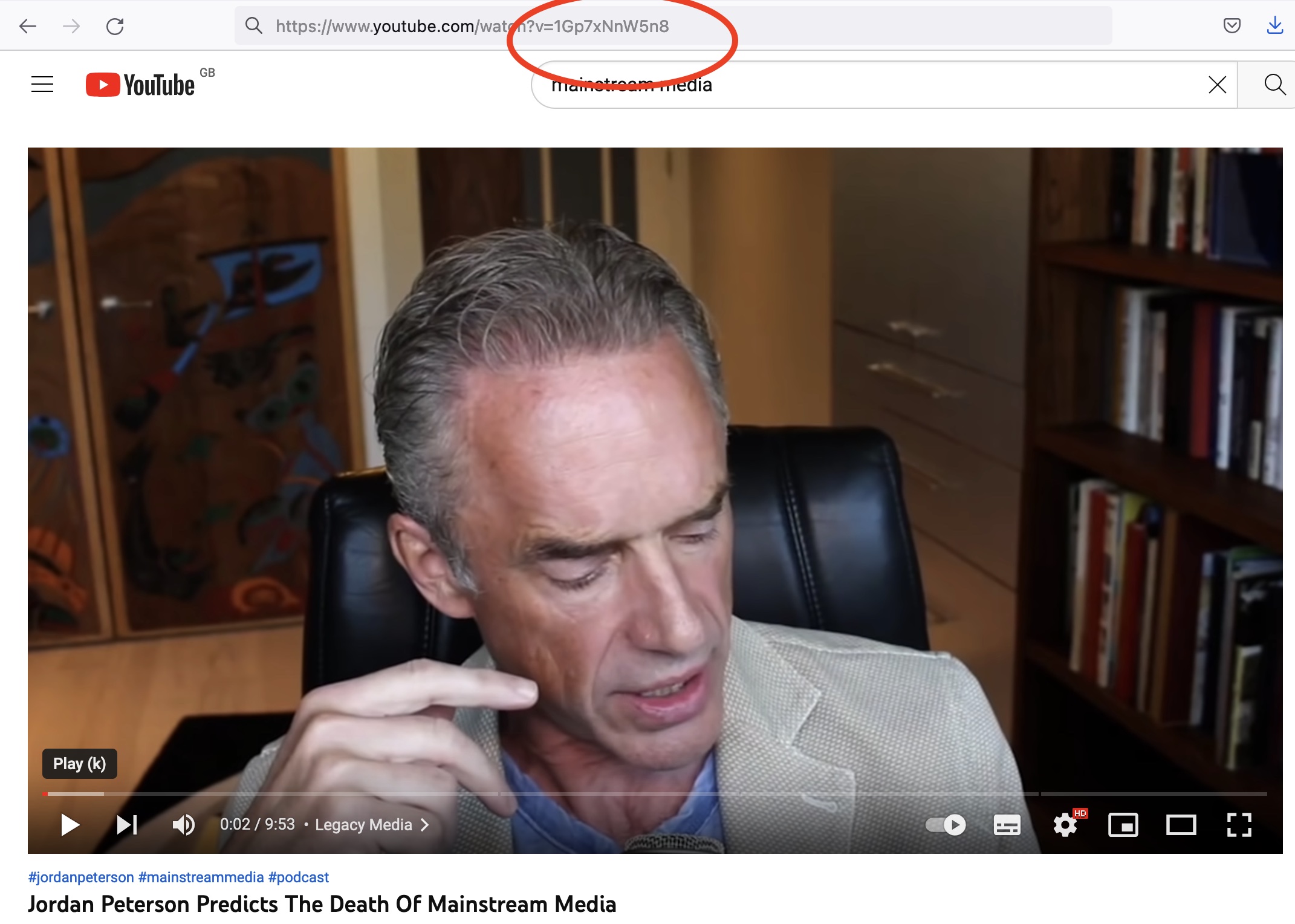

In this case, our seed video is a video by Jordan Peterson predicting the death of mainstream media. This is fairly “alternative” content and is actively taking a stance against mainstream media. So does this mean YouTube will learn to recommend us away from mainstream content?

library(tidyverse)

library(readxl)

devtools::install_github("soodoku/tuber") # need to install development version is there is problem with CRAN versions of the package functions

library(tuber)

yt_oauth("431484860847-1THISISNOTMYREALKEY7jlembpo3off4hhor.apps.googleusercontent.com","2niTHISISMADEUPTOO-l9NPUS90fp")

#get related videos

startvid <- "1Gp7xNnW5n8"

rel_vids <- get_related_videos(startvid, max_results = 50, safe_search = "none")In the above, we first take the unique identifying code string for the video. You can find this in the url for the video as shown below.

We can then collect the videos recommended on the basis of having this video as the seed video. We store these as the data.frame object rel_vids.

And we can have a look at the recommended videos on the basis of this seed video below.

It seems YouTube recommends us back a lot of videos relating to Jordan Peterson. Some of these are from more mainstream outlets; others are from more obscure sources.

23.5 Questions

Make your own request to the YouTube API for a different seed video.

Collect one video ID for each of the channels included in the resulting data

Write a for loop to collect recommended videos for each of these video IDs

23.6 Scraping

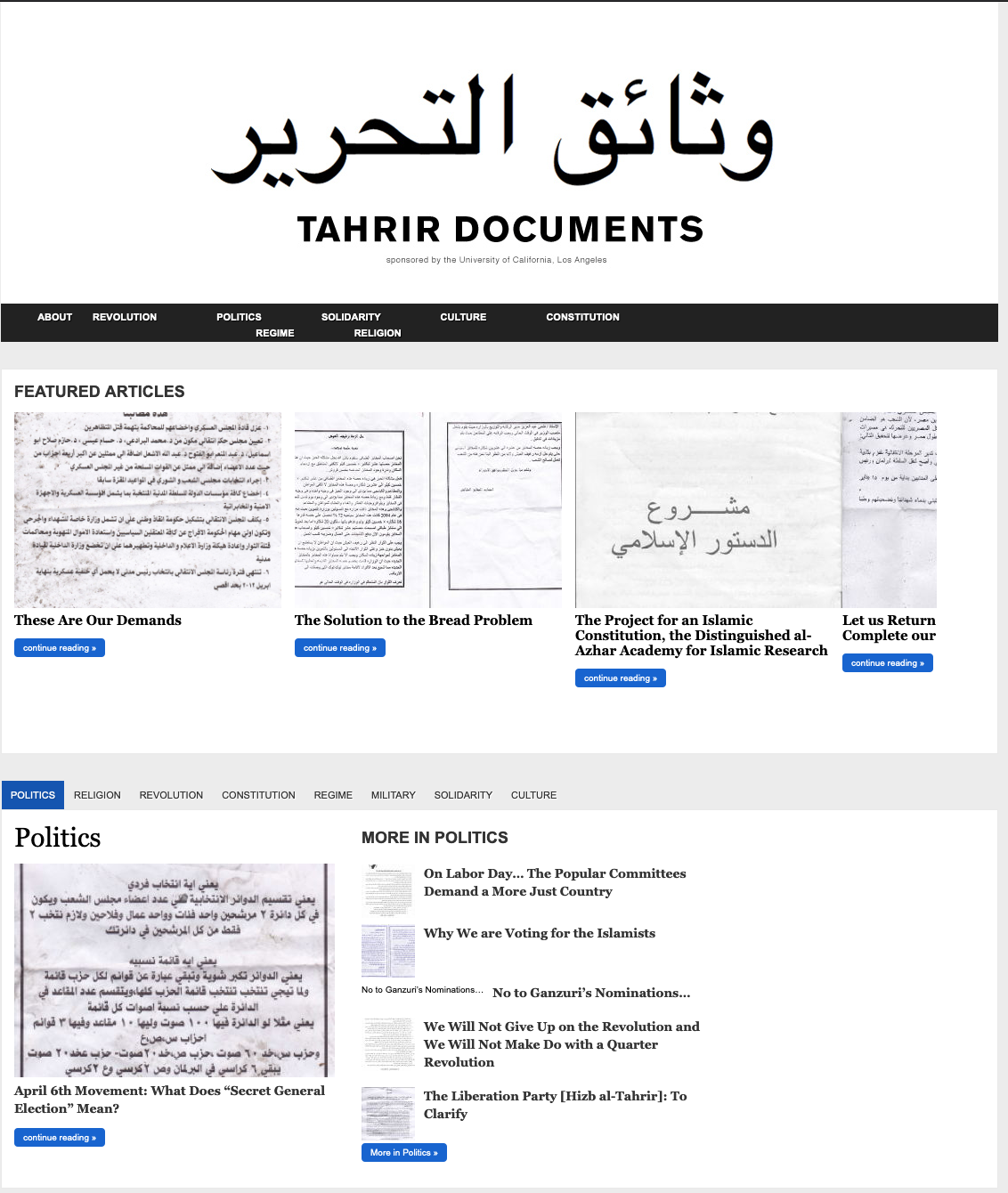

To practice this skill, we will use a series of webpages on the Internet Archive that host material collected at the Arab Spring protests in Egypt in 2011. The original website can be seen here and below.

Before proceeding, we’ll load the remaining packages we will need for this tutorial.

library(tidyverse) # loads dplyr, ggplot2, and others

library(ggthemes) # includes a set of themes to make your visualizations look nice!

library(readr) # more informative and easy way to import data

library(stringr) # to handle text elements

library(rvest) #for scrapingWe can download the final dataset we will produce with:

pamphdata <- read_csv("data/sampling/pamphlets_formatted_gsheets.csv")## Rows: 523 Columns: 8

## ── Column specification ─────────────────────────────────────────

## Delimiter: ","

## chr (6): title, text, tags, imageurl, imgID, image

## dbl (1): year

## date (1): date

##

## ℹ Use `spec()` to retrieve the full column specification for this data.

## ℹ Specify the column types or set `show_col_types = FALSE` to quiet this message.You can also view the formatted output of this scraping exercise, alongside images of the documents in question, in Google Sheets here.

If you’re working on this document from your own computer (“locally”) you can download the Tahrir documents data in the following way:

pamphdata <- read_csv("https://github.com/cjbarrie/CTA-ED/blob/main/data/sampling/pamphlets_formatted_gsheets.csv")Let’s have a look at what we will end up producing:

head(pamphdata)## # A tibble: 6 × 8

## title date year text tags imageurl imgID image

## <chr> <date> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr>

## 1 The Season o… 2011-03-30 2011 The … Soli… https:/… imgI… =Arr…

## 2 The Most Imp… 2011-03-30 2011 [Voi… Soli… https:/… imgI… <NA>

## 3 Yes it’s the… 2011-03-30 2011 [Voi… Soli… https:/… imgI… <NA>

## 4 The Revoluti… 2011-03-30 2011 [Voi… Revo… https:/… imgI… <NA>

## 5 Voice of the… 2011-03-30 2011 Febr… Revo… https:/… imgI… <NA>

## 6 We Are Still… 2011-03-29 2011 We A… Dema… https:/… imgI… <NA>We are going to return to the Internet Archived webpages to see how we can produce this final formatted dataset. The archived Tahrir Documents webpages can be accessed here.

We first want to expect how the contents of each webpage is stored.

When we scroll to the very bottom of the page, we see listed a number of hyperlinks to documents stored by month:

We will click through the documents stored for March and then click on the top listed pamphlet entitled “The Season of Anger Sets in Among the Arab Peoples.” You can access this here.

We will store this url to inspect the HTML it contains as follows:

url <- "https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130161341/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2011/03/voice-of-the-revolution-3-page-2/"

html <- read_html(url)

html## {html_document}

## <html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml" dir="ltr" lang="en-US">

## [1] <head profile="http://gmpg.org/xfn/11">\n<!-- Start Waybac ...

## [2] <body> \n<!--\n FILE ARCHIVED ON 16:13:41 ...Well, this isn’t particularly useful. Let’s now see how we can extract the text contained inside.

## [1] "\nif (window._WBWombatInit) {\n _wb_uc = new URL(\"http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2011/03/voice-of-the-revolution-3-page-2/\");\n wbinfo = {}\n wbinfo.url = \"http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2011/03/voice-of-the-revolution-3-page-2/\";\n wbinfo.timestamp = \"20120130161341\";\n wbinfo.request_ts = \"20120130161341\";\n wbinfo.prefix = \"https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/\";\n wbinfo.mod = \"\";\n wbinfo.is_framed = false;\n wbinfo.is_live = false;\n wbinfo.coll = \"2358\";\n wbinfo.proxy_magic = \"\";\n wbinfo.static_prefix = \"/static/\";\n wbinfo.enable_auto_fetch = true;\n wbinfo.auto_fetch_worker_prefix = \"https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/\";\n wbinfo.wombat_ts = \"20120130161341\";\n wbinfo.wombat_sec = \"1327940021\";\n wbinfo.wombat_scheme = ( _wb_uc.protocol || 'http').replace(/:$/, '');\n wbinfo.wombat_host = _wb_uc.host;\n wbinfo.wombat_opts = {\n no_rewrite_prefixes: [\n \"https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/\",\n \"//archive-it.org/\",\n \"https://partner.archive-it.org/\",\n ]\n };\n window._WBWombatInit(wbinfo);\n\n // variables useful for rulesengine rewrites from old ait-client_rewrite.js\n WB_RewriteUrl = _wb_wombat.rewrite_url;\n WB_ExtractOrig = _wb_wombat.extract_orig;\n WB_wombat_self_location = window.WB_wombat_location\n}\n The Season of Anger Sets in Among the Arab Peoples//<![CDATA[\n\t// Google Analytics for WordPress by Yoast v4.0.10 | http://yoast.com/wordpress/google-analytics/\n\tvar _gaq = _gaq || [];\n\t_gaq.push(['_setAccount','UA-7521051-7']);\n\t_gaq.push(['_trackPageview']);\n\t(function() {\n\t\tvar ga = document.createElement('script'); ga.type = 'text/javascript'; ga.async = true;\n\t\tga.src = ('https:' == document.location.protocol ? 'https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130161341/https://ssl' : 'https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130161341/http://www') + '.google-analytics.com/ga.js';\n\t\tvar s = document.getElementsByTagName('script')[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(ga, s);\n\t})();\n\t//]]>\nbody { background-color: #ececec; }\n \n\n\n\n\n \n \n\n \n \n \n \n \n\n \n \n \n \n \n\n\n \n \n About\nRevolution\nLogistics\n\tRevolutionary Newspapers\n\tDemands\n\tCalls to Protest\n\nPolitics\nWafd Party\n\tThe Popular Committees for the Defense of the Revolution\n\tThe Party of the Popular Socialist Alliance\n\tThe Muslim Brotherhood\n\tThe National Progressive Unionist Party (Hizb al-Tagammu’)\n\tThe Justice Party\n\tOther Parties\n\tThe Egyptian Communist Party\n\tCandidates\n\nSolidarity\nWorkers\n\tUnions\n\tPalestine\n\tMovements\n\tLibya\n\nCulture\nPoetry\n\tMedia\n\tSigns from Tahrir\n\tHealth\n\tFiction\n\nConstitution\nMarch Referendum\n\tTheory\n\tDostour Newsletters\n\tConstitution First Movement\n\nRegime\nMubarak and Family\n\tPolice\n\tPrisoners\n\tSecurity Forces\n\nReligion\nAl-Azhar\n\tCoptic Christians\n\tFamily\n\tMoral Conduct\n\tSalafism\n\tSectarian Strife\n\n\n \n \n\n \n\n \n \n \n \n \n\n \n \n \n \n \n \n The Season of Anger Sets in Among the Arab Peoples\n \n \n \n March 30, 2011 9:43 pm Solidarity no comments\n \n \n \n \n \n \n \n\nClick here to download the original.\nThe Season of Anger Sets in Among the Arab Peoples\n \nA member of the Algerian opposition warned the Arab rulers that the Tunisian revolution would initiate a revolutionary tsunami phenomenon that would sweep away their thrones. At the beginning of last December, the end of the dictatorial regimes began with successive protests against high prices in Algeria and Jordan. Then the Tunisian revolution demanded the fall of the regime. Algeria caught the ball of flames, and protests ignited again after having calmed for a time. Then after the Tunisian president was expelled, the revolution reached Egypt. And when Egyptians deposed Mubarak, the sparks proceeded to Algeria, Jordan, Yemen, Bahrain, and then Libya.\n \nThe issue is not one of infection; rather, the subjugated peoples discovered the potential of their own free will. The revolution in one country inspired the populations in other countries, for people imprison themselves in waiting, hoping and yearning, until their spirits emerge carrying the roar of anger that shakes thrones. Every population transfers the experience of other revolutions, borrowing their slogans—’the people want the fall of the regime,’ and ‘peaceful, peaceful’—and their tactics, like the Friday of Anger in Jordan and sit-ins held in major squares located in middle of the capital, such as Egypt’s Tahrir Square. Tunisian revolutionaries contacted Egyptians, providing them with some tactics to beat the regime’s machine, like spraying the windshields of armored cars with colors to paralyze and get the better of them.\n \nBeyond inspiration and transmitting experience, there is also solidarity, for the Tunisian revolution’s victory celebrations spread to Jordan and Egypt. And most of the Arab peoples participated in Egypt’s joy. There were many moving scenes, like the singing of the national anthem and the distribution of sweets and drinks in Jordan and Gaza in celebration of Mubarak’s deposal.\n \nHowever, the regimes that consolidate their interests over and against the people’s also rely on one another and exchange their experiences with oppression and harassment. And now confrontations are raging in Bahrain, Yemen, and Libya as mummified regimes committing increased acts of violence and brutal murder against the protesters. Just as Egypt’s extinct regime did, they use thugs with soft weaponry to transform the scene into bloody chaos. Meanwhile, Israel threatens chaos at the regional level in support of its spies, the Arab rulers, since the one who benefits most from the bowing down of the Arab peoples and their backwardness is none other than Israel.\n \n\nThe solidarity and support of the Arab revolutions for each other is the destiny of the Arab region and the only way to protect the interests and wealth of its peoples. With the extinct regime issuing threats—as if from another world—that Omar Suleiman, Mubarak, or Ria and Sikina will return, the duty to protect our revolution has doubled. Our resistance won’t simply bring about complete, permanent victory for our own revolution; it will also support the revolutions of other populations who support us in turn. This is our duty and our destiny. For the populations who were long patient, the path of regression to what came before was no longer available. Their victory will soon be achieved through their resistance and free will.\n\n \n________________________\nAcquired March 2011\nTranslated by Yasmeen Mekawy\nTranslation reviewed by Emily Drumsta\n \n \nRelated posts:Call for the Military to Impeach MubarakA Very Important Proposal from the Coalition of the Youth of the Revolution in the City of Matai–al-...The Struggle Movement \t\t\t\t \n \n \n \n \n \n Share this post\n \n \n \n \n \n \n \n \n \n \n \n \n \n \n \n « The Most Important Workers’ Protests The Popular Alliance Party: Foundational Declaration » \n \n\n\n\n\n\n\n\n\n\n \n \n \n \n \n \n Follow Us on Facebook & Twitter About\t\t\tTahrir Documents is an ongoing effort to archive and translate activist papers from the 2011 Egyptian uprising and its aftermath. Materials are collected from demonstrations in Cairo’s Tahrir Square and published in complete English translation alongside scans of the original documents. The project is not affiliated with any political organization, Egyptian or otherwise.\nFor more information please contact tahrirdocuments@gmail.com\n\n\t\t CategoriesAl-Azhar\nCalls to Protest\nCandidates\nConstitution\nConstitution First Movement\nCulture\nDemands\nDostour Newsletters\nFamily\nFiction\nHealth\nLibya\nLogistics\nMarch Referendum\nMedia\nMilitary\nMilitary Tribunals\nMoral Conduct\nMovements\nMubarak and Family\nOther Parties\nPalestine\nPoetry\nPolice\nPolitics\nPrisoners\nRegime\nReligion\nRevolution\nRevolutionary Newspapers\nSalafism\nSectarian Strife\nSecurity Forces\nSigns from Tahrir\nSolidarity\nThe Egyptian Communist Party\nThe Justice Party\nThe Muslim Brotherhood\nThe National Progressive Unionist Party (Hizb al-Tagammu')\nTheory\nThe Party of the Popular Socialist Alliance\nThe Popular Committees for the Defense of the Revolution\nUnions\nWafd Party\nWorkers\n \n \n \n \n \n\n \n \n\n\n \n \n \n\n \n\n Archives\t\tJanuary 2012\n\tDecember 2011\n\tNovember 2011\n\tOctober 2011\n\tSeptember 2011\n\tAugust 2011\n\tJuly 2011\n\tJune 2011\n\tMay 2011\n\tApril 2011\n\tMarch 2011\n\t\t \n\n\t \n\t \n\t \n\t \n\t Tahrir Documents\t\tAbout\nContact\n\t\t \t \n\t \n\t \n\t \n\t \n\t \n\t \t \n\t \n\t \n\n\t \n\t \n\t Search\n\tSearch for:\n\t\n\t \t \n\t \n\t \n\t \n\t \n\n \n \n \n \n \n Designed by \n Copyright © 2012 Tahrir Documents. All rights reserved.\n \n \n \n\n\n\n\n var _gaq = _gaq || [];\n _gaq.push(['_setAccount', 'UA-7521051-7']);\n _gaq.push(['_trackPageview']);\n\n (function() {\n var ga = document.createElement('script'); ga.type = 'text/javascript'; ga.async = true;\n ga.src = ('https:' == document.location.protocol ? 'https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130161341/https://ssl' : 'https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130161341/http://www') + '.google-analytics.com/ga.js';\n var s = document.getElementsByTagName('script')[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(ga, s);\n })();\n\n"Well this looks pretty terrifying now…

We need a way of quickly identifying where the relevant text is so that we can specify this when we are scraping. The most widely-used tool to achieve this is the “Selector Gadget” Chrome Extension. You can add this to your browser for free here.

The tool works by allowing the user to point and click on elements of a webpage (or “CSS selectors”). Unlike alternatives, such as “Inspect Element” browser tools, we are easily able to see how the webpage item is contained within CSS selectors (rather than HTML tags alone), which is easier to parse.

We can do this with our Tahrir documents as below:

So now we know that the main text of the translated document is contained between “p” HTML tags. To identify the text between these HTML tags we can run:

pagetext <- html %>%

html_elements("p") %>%

html_text(trim=TRUE)

pagetext## [1] ""

## [2] ""

## [3] "Click here to download the original."

## [4] "The Season of Anger Sets in Among the Arab Peoples"

## [5] ""

## [6] "A member of the Algerian opposition warned the Arab rulers that the Tunisian revolution would initiate a revolutionary tsunami phenomenon that would sweep away their thrones. At the beginning of last December, the end of the dictatorial regimes began with successive protests against high prices in Algeria and Jordan. Then the Tunisian revolution demanded the fall of the regime. Algeria caught the ball of flames, and protests ignited again after having calmed for a time. Then after the Tunisian president was expelled, the revolution reached Egypt. And when Egyptians deposed Mubarak, the sparks proceeded to Algeria, Jordan, Yemen, Bahrain, and then Libya."

## [7] ""

## [8] "The issue is not one of infection; rather, the subjugated peoples discovered the potential of their own free will. The revolution in one country inspired the populations in other countries, for people imprison themselves in waiting, hoping and yearning, until their spirits emerge carrying the roar of anger that shakes thrones. Every population transfers the experience of other revolutions, borrowing their slogans—’the people want the fall of the regime,’ and ‘peaceful, peaceful’—and their tactics, like the Friday of Anger in Jordan and sit-ins held in major squares located in middle of the capital, such as Egypt’s Tahrir Square. Tunisian revolutionaries contacted Egyptians, providing them with some tactics to beat the regime’s machine, like spraying the windshields of armored cars with colors to paralyze and get the better of them."

## [9] ""

## [10] "Beyond inspiration and transmitting experience, there is also solidarity, for the Tunisian revolution’s victory celebrations spread to Jordan and Egypt. And most of the Arab peoples participated in Egypt’s joy. There were many moving scenes, like the singing of the national anthem and the distribution of sweets and drinks in Jordan and Gaza in celebration of Mubarak’s deposal."

## [11] ""

## [12] "However, the regimes that consolidate their interests over and against the people’s also rely on one another and exchange their experiences with oppression and harassment. And now confrontations are raging in Bahrain, Yemen, and Libya as mummified regimes committing increased acts of violence and brutal murder against the protesters. Just as Egypt’s extinct regime did, they use thugs with soft weaponry to transform the scene into bloody chaos. Meanwhile, Israel threatens chaos at the regional level in support of its spies, the Arab rulers, since the one who benefits most from the bowing down of the Arab peoples and their backwardness is none other than Israel."

## [13] ""

## [14] "The solidarity and support of the Arab revolutions for each other is the destiny of the Arab region and the only way to protect the interests and wealth of its peoples. With the extinct regime issuing threats—as if from another world—that Omar Suleiman, Mubarak, or Ria and Sikina will return, the duty to protect our revolution has doubled. Our resistance won’t simply bring about complete, permanent victory for our own revolution; it will also support the revolutions of other populations who support us in turn. This is our duty and our destiny. For the populations who were long patient, the path of regression to what came before was no longer available. Their victory will soon be achieved through their resistance and free will."

## [15] ""

## [16] "________________________"

## [17] "Acquired March 2011"

## [18] "Translated by Yasmeen Mekawy"

## [19] "Translation reviewed by Emily Drumsta"

## [20] ""

## [21] ""

## [22] "« The Most Important Workers’ Protests The Popular Alliance Party: Foundational Declaration »"

## [23] "Tahrir Documents is an ongoing effort to archive and translate activist papers from the 2011 Egyptian uprising and its aftermath. Materials are collected from demonstrations in Cairo’s Tahrir Square and published in complete English translation alongside scans of the original documents. The project is not affiliated with any political organization, Egyptian or otherwise."

## [24] "For more information please contact tahrirdocuments@gmail.com"

## [25] "Designed by"

## [26] "Copyright © 2012 Tahrir Documents. All rights reserved.", which looks quite a lot more manageable…!

What is happening here? Essentially, the html_elements() function is scanning the page and collecting all HTML elements contained between <p> tags, which we collect using the “p” CSS selector. We are then just grabbing the text contained in this part of the page with the html_text() function.

So this gives us one way of capturing the text, but what about if we wanted to get other elements of the document, for example the date or the tags attributed to each document? Well we can do the same thing here too. Let’s take the example of getting the date:

We see here that the date is identified by the “.calendar” CSS selector and so we enter this into the same html_elements() function as before:

pagedate <- html %>%

html_elements(".calendar") %>%

html_text(trim=TRUE)

pagedate## [1] "March 30, 2011 9:43 pm"Of course, this is all well and good, but we also need a way of doing this at scale—we can’t just keep repeating the same process for every page we find as this wouldn’t be much quicker than just copy pasting. So how can we do this? Well we need first to understand the URL structure of the website in question.

When we scroll down the page we see listed a number of documents. Each of these directs to an individual pamphlet distributed at protests during the 2011 Egyptian Revolution.

Click on one of these and see how the URL changes.

We see that if our starting URL was:

https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130135111/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/Then if we click on March 2011, the first month for which we have documents, we see that the url becomes:

https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130143023/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2011/03/, for August 2011 it becomes:

https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130142155/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2011/08/, and for January 2012 it becomes:

https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130142014/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2012/01/We notice that for each month, the URL changes with the addition of month and year between back slashes at the end or the URL. In the next section, we will go through how to efficiently create a set of URLs to loop through and retrieve the information contained in each individual webpage.

We are going to want to retrieve the text of documents archived for each month. As such, our first task is to store each of these webpages as a series of strings. We could do this manually by, for example, pasting year and month strings to the end of each URL for each month from March, 2011 to January, 2012:

url <- "https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130143023/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/"

url1 <- paste0(url,"2011/03/")

url2 <- paste0(url,"2011/04/")

url3 <- paste0(url,"2011/04/")

#etc...

urls <- c(url1, url2, url3)But this wouldn’t be particularly efficient…

Instead, we can wrap all of this in a loop.

urls <- character(0)

for (i in 3:13) {

url <- "https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130143023/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/"

newurl <- ifelse(i <10, paste0(url,"2011/0",i,"/"),

ifelse(i>=10 & i<=12 , paste0(url,"2011/",i,"/"),

paste0(url,"2012/01/")))

urls <- c(urls, newurl)

}What’s going on here? Well, we are first specifying the starting URL as above. We are then iterating through the numbers 3 to 13. And we are telling R to take the new URL and then, depending on the number in the loop we are on, to take the base starting url— https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130143023/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/ — and to paste on the end of it the string “2011/0”, then the number of the loop we are on, and then “/”. So, for the first “i” in the loop—the number 3—then we are effectively calling the equivalent of:

i <- 3

url <- "https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130143023/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/"

newurl <- paste0(url,"2011/0",i,"/")Which gives:

## [1] "https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130143023/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2011/03/"In the above, the ifelse() commands are simply telling R: if i (the number of the loop we are on) is less than 10 then paste0(url,"2011/0",i,"/"); i.e., if i is less than 10 then paste “2011/0”, then “i” and then “/”. So for the number 3 this becomes:

"https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130143023/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2011/03/"

, and for the number 4 this becomes

"https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130143023/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2011/04/"

If, however, i>=10 & i<=12 (i is greater than or equal to 10 and less than or equal to 12) then we are calling paste0(url,"2011/",i,"/") because here we do not need the first “0” in the months.

Finally, if (else) i is greater than 12 then we are calling paste0(url,"2012/01/"). For this last call, notice, we do not have to specify whether i is greater than or equal to 12 because we are wrapping everything in ifelse() commands. With ifelse() calls like this, we are telling R if x “meets condition” then do y, otherwise do z. When we are wrapping multiple ifelse() calls within each other, we are effectively telling R if x “meets condition” then do y, or if x “meets other condition” then do z, otherwise do a. So here, the “otherwise do a” part of the ifelse() calls is saying: if i is not less than 10, and is not between 10 and 12, then paste “2012/01/” to the end of the URL.

Got it? I didn’t even get it on first reading… and I wrote it. The best way to understand what is going on is to run this code yourself and look at what each part is doing.

So now we have our list of URLs for each month. What next?

Well if we go onto the page of a particular month, let’s say March, we will see that the page has multiple paginated tabs at the bottom. Let’s see what happens to the URL when we click on one of these:

We see that if our starting point URL for March, as above, was:

https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130143023/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2011/03/When we click through to page 2 it becomes:

https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130163651/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2011/03/page/2/And for page 3 it becomes:

https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130163651/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2011/03/page/3/We can see pretty clearly that as we navigate through each page, there appears appended to the URL the string “page/2/” and “page/3/”. So this shouldn’t be too tricky to add to our list of URLs. But we want to avoid having to manually click through the archive for each month to figure out how many pagination tabs are at the bottom of each page.

Fortunately, we don’t have to. Using the “Selector Gadget” tool again we can automate this process by grabbing the highest number that appears in the pagination bar for each month’s pages. The code below achieves this:

urlpages_all <- character(0) #create empty character string to deposit our final set of urls

urlpages <- character(0) #create empty character string to deposit our urls for each page of each month

for (i in seq_along(urls)) { #for loop for each url stored above

url <- urls[i] #take the first url from the vector of urls created above

html <- read_html(url) #read the html

pages <- html %>%

html_elements(".page") %>% #grab the page element

html_text() #convert to text

pageints <- as.integer(pages) #convert to set of integers

npages <- max(pageints, na.rm = T) #get number of highest integer

for (j in 1:npages) { #for loop for each of 1:highest page integer for that month's url

newurl <- paste0(url,"page/",j,"/") #create new url by pasting "page/" and then the number of that page, and then "/", matching the url structure identified above

urlpages <- c(urlpages, newurl) #bind with previously created page urls for each month

}

urlpages_all <- c(urlpages_all, urlpages) #bind the monthly page by page urls together

urlpages <- character(0) #empty urlpages for next iteration of the first for loop

urlpages_all <- gsub("page/1/", "", urlpages_all) #get rid of page/1/ as not needed

}What’s going on here? Well, in the first two lines, we are simply creating an empty character string that we’re going to populate in the subsequent loop. Remember that we have a set of eleven starting URLs for each of months archived on this webpage.

So in the code beginning for (i in seq_along(files) we saying, similar to above, for the beginning url to the end url, do the following in a loop: first, read in the url with url <- urls[i] then read the html it contains with html <- read_html(url).

After this line, we are getting the pages as a character vector of page numbers by calling the html_elements() function on the “.page” tag. this gives a series of pages stored as e.g. “1” “2” “3”.

In order to be able to see how many there are, we need to extract the highest number that appears in this string. To do this, we first need to reformat it as an “integer” object rather than a “character” object so that R can recognize that these are numbers. So we call pageints <- as.integer(pages). Then we get the maximum by simply calling: npages <- max(pageints, na.rm = T).

In the next part of the loop, we are taking the new information we have stored as “npages,” i.e., the number of pagination tabs for each month, and telling R: for each of these pages, define a new url by adding “page/” then the number of the pagination tab “j”, and then “/”. After we’ve bound all of these together, we get a list of URLs that look like this:

head(urlpages_all)## [1] "https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130143023/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2011/03/"

## [2] "https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130143023/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2011/03/page/2/"

## [3] "https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130143023/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2011/03/page/3/"

## [4] "https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130143023/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2011/03/page/4/"

## [5] "https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130143023/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2011/03/page/5/"

## [6] "https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130143023/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2011/03/page/6/"So what next?

The next step is to get the URLs for each of the documents contained in the archive for each month. How do we do this? Well, we can once again use the “Selector Gadget” tool to work this out. For the main landing pages of each month, we see listed, as below, each document in a list. For each of these documents, we see that the title, which links to the revolutionary leaflet in question, has two CSS selectors: “h2” and “.post”.

We can again pass these tags through html_elements() to grab what’s contained inside. We can then grab what’s contained inside these by extracting the “children” of these classes. In essence, this just means a lower level tag: tags can have tags within tags and these flow downwards like a family tree (hence the name, I suppose).

So one of the “children” of this HTML tag is the link contained inside, which we can get with calling html_children() followed by specifying that we want the specific attribute of the web link it encloses with html_attr("href"). The subsequent lines then just remove extraneous information.

The complete loop, then, to retrieve the URL of the page for every leaflet contained on this website is:

#GET URLS FOR EACH PAMPHLET

pamlinks_all <- character(0)

for (i in seq_along(urlpages_all)) {

url <- urlpages_all[i]

html <- read_html(url)

links <- html_elements(html, ".post , h2") %>%

html_children() %>%

html_attr("href") %>%

na.omit() %>%

`attributes<-`(NULL)

pamlinks_all <- c(pamlinks_all, links)

}Which gives us:

head(pamlinks_all)## [1] "https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130143023/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2011/03/voice-of-the-revolution-3-page-2/"

## [2] "https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130143023/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2011/03/the-most-important-workers-protests/"

## [3] "https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130143023/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2011/03/yes-its-the-workers-and-employees-right-to-strike/"

## [4] "https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130143023/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2011/03/the-revolution-is-still-ongoing-2/"

## [5] "https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130143023/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2011/03/voice-of-the-revolution-the-revolution-is-still-ongoing/"

## [6] "https://wayback.archive-it.org/2358/20120130143023/http://www.tahrirdocuments.org/2011/03/we-are-still-continuing-until-victory/"

length(pamlinks_all)## [1] 523We see now that we have collected all 523 separate URLs for every revolutionary leaflet contained on these pages. Now we’re in a great position to be able to crawl each page and collect the information we need. This final loop is all we need to go through each URL we’re interested in and collect relevant information on document text, title, date, tags, and the URL to the image of the revolutionary literature itself.

See if you can work out yourselves how each part of this is fitting together. NOTE: if you want to run the final loop on your own machines it will take several hours to complete.

df_empty <- data.frame()

for (i in seq_along(pamlinks_all)) {

url <- pamlinks_all[i]

html <- read_html(url)

cat("Collecting url number ",i,": ", url, "\n")

error <- tryCatch(html <- read_html(url),

error=function(e) e)

if (inherits(error, 'error')) {

df <- data.frame(title = NA,

date = NA,

text = NA,

imageurl = NA,

tags = NA)

next

}

df <- data.frame(matrix(ncol=0, nrow=length(1)))

#get titles

titles <- html_elements(html, ".title") %>%

html_text(trim=TRUE)

title <- titles[1]

df$title <- title

#get date

date <- html_elements(html, ".calendar") %>%

html_text(trim=TRUE)

df$date <- date

#get text

textsep <- html_elements(html, "p") %>%

html_text(trim=TRUE)

text <- paste(textsep, collapse = ",")

df$text <- text

#get tags

pamtags <- html_elements(html, ".category") %>%

html_text(trim=TRUE)

df$tags <- pamtags

#get link to original pamphlet image

elements_other <- html_elements(html, "a") %>%

html_children()

url_element <- as.character(elements_other[2])

imgurl <- str_extract(url_element, "src=\\S+")

imgurl <- substr(imgurl, 6, (nchar(imgurl)-1))

df$imageurl <- imgurl

df_empty <- rbind(df_empty, df)

}And now… we’re pretty much there…back where we started!

23.7 Speech to text

There are some R packages that allow the user to connect to the Google Speech-to-Text engine (billing information required to access). You can find such a package here but it doesn’t seem to be readily maintained. There is a far wider range of options if you are open to using Python: see, e.g.: here.

Here, we’re instead going to do the next best thing: capture text that has already been converted from speech. Here, we’re going to be collecting the automated English captioning from YouTube videos. For this, we will use the R package youtubecaption. Because this package connects to an already existing Python package under the hood, you’ll need to have a Conda environment installed. You can download Anaconda Individual Edition here.

And to grab the text from a video is as simple as below.

library(youtubecaption)

url <- "https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cpbtcsGE0OA"

caption <- get_caption(url)

captionAnd if you wanted to the same thing in Python you would do the following.

23.8 OCR

The last major technique that might be of interest for extracting text is Optical Character Recognition (OCR). This is a technique that reads in image files (e.g., .jpg or .png or .pdf) automatically extracts the text contained therein.

A very good package in R for extracting text from images is daiR, details of which can be found here. This connects again to the Google Cloud Engine (and thus requires billing info.) but it won’t charge you until you’ve spent your first free $300 of credit. This will take a while to spend so you have a good deal amount of tokens before you start incurring expenses.

You can consult here for info. on setting up your Google Cloud service account.

Once you have done this you’ll be ready to connect to the Google Cloud Engine.